Last time, we were comparing the elements that create a jump-scare to the elements that create an entire horror movie. Today, we’re going to expand on that and talk about creating player mind-sets in horror games.

Finding primary sources for this is difficult, because horror experiences are so personal. I can tell you what I was thinking at a given moment of gameplay, but it might not be the norm. We can discuss what designers wanted their players to feel, but whether or not that translates to the player experience is going to depend on a lot of factors external to the design.

So, we’re going to go broad and stick with a few concrete perspectives. To do that, we’re going to start with Dead Space 3.

Now, we all know the crafting system in Dead Space 3 rocked our immersion with its micro-transaction frippery, but is that the only issue with it? I would argue that it also creates entirely the wrong mind-set in the player. When you’re crafting a weapon in DS3, what are you thinking about?

Well, I don’t know about you, but I’m thinking about how much damage it’s going to do. I’m thinking about how many pieces they’ll fly into. Or, I’m considering the merits of perpetual-stasis ripper-saws against those of a glowing death-ball cannon. If you watched my Painkiller video of yore, you’ll have probably figured out my point already: in none of the scenarios I’m considering am I the prey.

I’m preparing for battle, so I’m preparing to hunt, or, at least, to take down a dangerous opponent. The dynamic I’m thinking in is that of a predator. That’s empowering; that’s the opposite of the way I should be thinking. I should be thinking, “I hope this will keep me alive, but I’m not sure if it will.” If I’m going to min-max, then it should be for all the right reasons.

But my question is, if you’re already thinking about your strength and how to combat an opponent, aren’t you already in the wrong mind-set? This is one of the things that makes horror RPGs so questionable to me: RPG elements are usually about growth towards success and away from dis-empowerment.

The way we usually employ leveling systems isn’t going to cut it; we need our level-ups to reinforce our position in the monster dynamic. There are several ways to do this. One way is simply to ensure that your growth never makes you equal to the monsters. This can be accomplished by simply making the monsters more powerful, but then it’s pretty hard to distinguish between standard monster progression and an atmosphere of oppression. Lulz.

Again, though, if we’re in that mind-set, then we’ve already lost the first battle. Let’s step back: what does our level-up system tell the player about how they’re growing? If you can grow in strength, then your ability to combat the enemy grows, as well. But, what if you grow in pivoting speed? I know it sounds silly next to Strength, but that’s why we just don’t include Strength.

Our character could grow in areas that reinforce its prey-like nature. The ability to pivot quicker or sprint longer would give the player the tools to escape enemies more easily, but it wouldn’t make the escape itself trivial. An ability that allows the player to sense their enemies seems like a good idea, but that also increases the player’s ability to combat the enemy.

Another thing to remember, here, is not to allow the level-up mechanics to interact with the puzzles or the challenges in any way that makes them easier. Doing that gives the player Avatar-strength, which is exactly what we’re avoiding in the combat. The message should be: your growth helps you survive, not succeed.

For example, let’s say we give players the ability to unlock an emergency u-turn button. That ability shouldn’t then interact with some puzzle that requires that you turn around more quickly, unless the speed with which you turn has no bearing on the challenge.

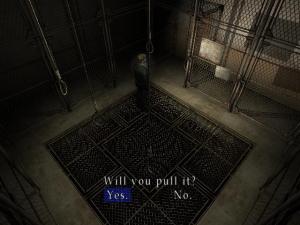

Let it be a convenience. What do I mean? Well, if you’re doing a riddle that requires that you pull on six hang-man’s nooses that are spaced around a room, then quick-turn lets you navigate to them more easily, if you’re in a third-person shooter. However, if there’s a timed-element, then quick-turn makes this portion easier by making the navigation easier.

Now, this can be contextual, as well. If the puzzle is just a random timed puzzle for reasons, then it’s not really a big deal that your level-progression assisted you through it. However, if it’s a timed puzzle because the forces of darkness are slowly possessing your soul, then your level-progression has assisted you in fighting them, altering the dynamic once more.

Growing empowered doesn’t have to be a negative aspect of a horror game. It could always be shown to be an utter illusion, but, since it’s already an illusion, it’s difficult to experience the difference, at times. However, if progression leads you towards something awful, then we’ve altered the dynamic, again.

Think about Cthulhu. (but not too hard) As an entity, it is beyond grasping. However, in their studies of Cthulhu and the Occult, many adventurers find fantastic powers and strange, overwhelming artifacts. The deeper an adventurer quaffs, the madder it becomes. That’s another way to look at a power-progression.

Let’s say we’re in a house with a small ghost. Every day, that ghost grows slightly in power. In order to combat that ghost, we’ve got to learn about it and grow in power, as well. However, in order to grow in power, we must make sinister deals with Otherworldly creatures. These deals let a little bit of something slip through and we’re suddenly racing our madness with our intellect.

I envision this as a haunting-Occult sim that grows in insanity as you make deals with more and greater numbers of spirits. I’d include a Pact system that would eventually allow you to banish the evil from your house, but only after you’ve endured some messed-up shit and if you don’t die. However, it could also be a platformer that grows in complexity as you begin seeing more and more of the spirits populating the levels. You could probably get some funky level-replay value out of that. Remember the ! blocks in Super Mario World? Like that but with demons.

My point isn’t necessarily the gameplay: my point is the player mind-set. We must never stop asking: how do the systems we’re utilizing work together to influence how the player is thinking about their gameplay experience and, thus, their choices? That experience is where we need to concentrate our unnerving efforts: a frightening back-drop is nothing without it.

Speaking of backdrops, what about those environments and our relationship to them? Well, that usually depends on the systems in the game. If you’ve got a standard physics system, then you and the floor are well-acquainted. If you can swim, then water’s your buddy, guy! How about stealth mechanics? Shadows are your friend! And barrels. I like hiding behind barrels.

Think about how your relationship to the environment and the creatures changes between Outlast and Amnesia. Both of these games are about exploring the creepy-dark and finding baddies therein, but Amnesia has a stealth mechanic and Outlast has a hiding mechanic.

If you’re cornered in Outlast, then you can make a break for the next bed or locker and hide there. There aren’t really a lot of decisions to make about that: you just sprint and hide when you’re out of LoS. That’s about as much as you need to think about the environment, and that’s about as much as I did think about the environment.

However, in Amnesia, where every box might hide you and every shadow conceal you, you’re paying attention to the environment. You’re thinking about what the monster can see. You’re engaged with your surroundings. Yes, not being able to look at the creature helps, but only because you’re concerned about what the creature can see, so you’re thinking about the creature.

If you’re just thinking about avoiding the creature, then you’re not really threatened by it, because you’re not thinking of it as a threat. You’re thinking of it as an obstacle. You don’t think of its parameters, because they never come into play. You just react. See monster, run out of sight, hide, repeat. Or, see monster, stay out of sight, use sounds to avoid it, repeat.

A monster in Amnesia is an artificial intelligence to be played around. There are unknowns in its programming and risks you can take. You can successfully stack two boxes on top of each other and cower in a corner without knowing if that will hide you. That’s a qualitatively different experience to picking a locker to crouch in for a while before being found or not. One’s a coin-flip, the other’s a die roll.

For our player, the math behind it is not as important as the experience. That experience informs their mind-set, which informs their choices, which folds back in on their experience. Yes, that is a conceptual cluster-fuck, but we’re self-aware beings, so you weren’t expecting an easy answer, now, were you?

In any event, this is just a handful of perspectives. As I said last time, horror is like a finely-tuned melody. Any one of these elements that I’ve discussed, in good light or bad, can be part of a successful horror experience. The difference lies in how well the pieces fit together. It’s a difficult puzzle to navigate; I’ll see you on the other side.